“IG what?!” is very often the response women get from healthcare professionals when they try to explain that Insufficient Glandular Tissue (IGT) might be the reason why they appear not to have a full milk supply. I don’t say this to disparage healthcare professionals, but to highlight the fact that relatively little is known about IGT (also sometimes referred to as mammary hypoplasia) and that women very often struggle to find doctors who know anything about the condition or are able to provide them with answers as to why they might have it. IGT is real though, has not been invented by South Dublin mums, and it is documented in the literature going as far back as 1958 when a study of 900 breastfeeding women found that 4% were unable to breastfeed due to insufficient glandular development (Deem, 1958b).

I have a particular interest in low milk supply. I’m currently doing research as part of an MSc. on women’s experiences of breastfeeding with primary low milk supply – finishing May 22 (hopefully!) and I plan to publish my research at some stage, watch this space. I see a lot of clients in private practice who have low milk supply and I estimate that around 90% of them have IGT. It’s not particularly rare. It is a thing, as they say, and the limited studies that do exist on it estimate a prevalence of around 5%, perhaps even a little higher. Please note: IGT often does not become apparent until 2 – 3 weeks postpartum when a baby fails to gain weight appropriately, so if you work in a hospital setting you might not see it.

As a lactation consultant I don’t diagnose IGT. I don’t diagnose anything – I leave that to doctors. However, when I see a client who presents with possible primary low milk supply, I do a full health history, assess a feed, look at the baby, assess the mother’s breasts (if she if happy for me to do so), and get as much detail as I can about the baby’s birth and the mother’s breastfeeding experience to date. Sometimes all of this points to IGT. It is often referred to as a “diagnosis of exclusion”, meaning all other causes of low milk supply should be excluded first, before determining that IGT is the most probable cause. There are certain characteristics that breasts lacking glandular tissue present with; wide spacing, bulbous areolae, asymmetry and a tubular shape (sort of long, not as round as your average breast). However, it can never be assumed that breasts that have some or all of these markers will not be able to produce a full milk supply. In my experience I find that most women with IGT will make somewhere between 50 and 90% of the milk their baby needs, which is fantastic! With skilled and sensitive help and the right kind of support, women with IGT CAN breastfeed! They just probably need to supplement their baby with some extra milk. How they do this is up to them. I present women with options – some opt to supplement using a bottle, while some prefer to supplement at the breast using any one of a number of devices (eg homemade SNS with PVC feeding tube, Medela SNS, Haakaa feeding tube or the Lactaid system). I plan to do another blog on at-the-breast-supplementation at some stage. I find that one of the big difficulties women with IGT face though, is lack of information, and unhelpful advice. Often they will have one person telling them to “just give formula” and that “some women can’t breastfeed” and another telling them “it’ll be grand, just keep feeding and doing skin-to-skin”, which suffice to say is NOT helpful to a mother who knows she cannot make enough milk to exclusively breastfeed. So, I started a low milk supply support group on Zoom last September to provide support to mums breastfeeding with low milk supply. It is on every second Monday. I wasn’t sure how it would work, but it’s working! I facilitate and provide some information and guidance, but for the most part the mums look after each other and I know that one of the biggest benefits people attending get is that they realise they are not alone.

Anyway, I’m getting sidetracked. The reason I actually decided to do this blog was to share some information about IGT, what is known and what isn’t. So here goes:

Insufficient glandular tissue (IGT), also commonly referred to as mammary or breast hypoplasia, is defined as insufficient glandular or milk-producing tissue to produce enough milk to support adequate infant growth and development (Neifert, Seacat and Jobe, 1985). The aetiology of IGT is not clear, but there are theories that it could be genetic or caused by oestrogenic environmental exposure in certain agricultural settings (Arbour and Kessler, 2013a). There is also some evidence that breast growth and development in utero and during puberty could be inhibited by androgens (Dimitrakakis and Bondy, 2009). Menstrual disorders such as delayed menarche or amenorrhea during puberty can inhibit normal breast development and result in IGT. Breast development also depends on tight regulation of zinc metabolism. Lee et al., (2015) discovered from their research on mice that loss of the zinc transporter ZnT2 resulted in mammary hypoplasia and failed lactogenesis II, but concluded that further research is required in human subjects. More recently, Kam, Bernhardt, Ingman et al., (2021a) conducted a systematic review of modern, exogeneous exposures associated with mammary gland development. They found that both an obesogenic diet and certain endocrine disrupting chemicals can alter mammary gland development and in turn impact future lactation capacity.

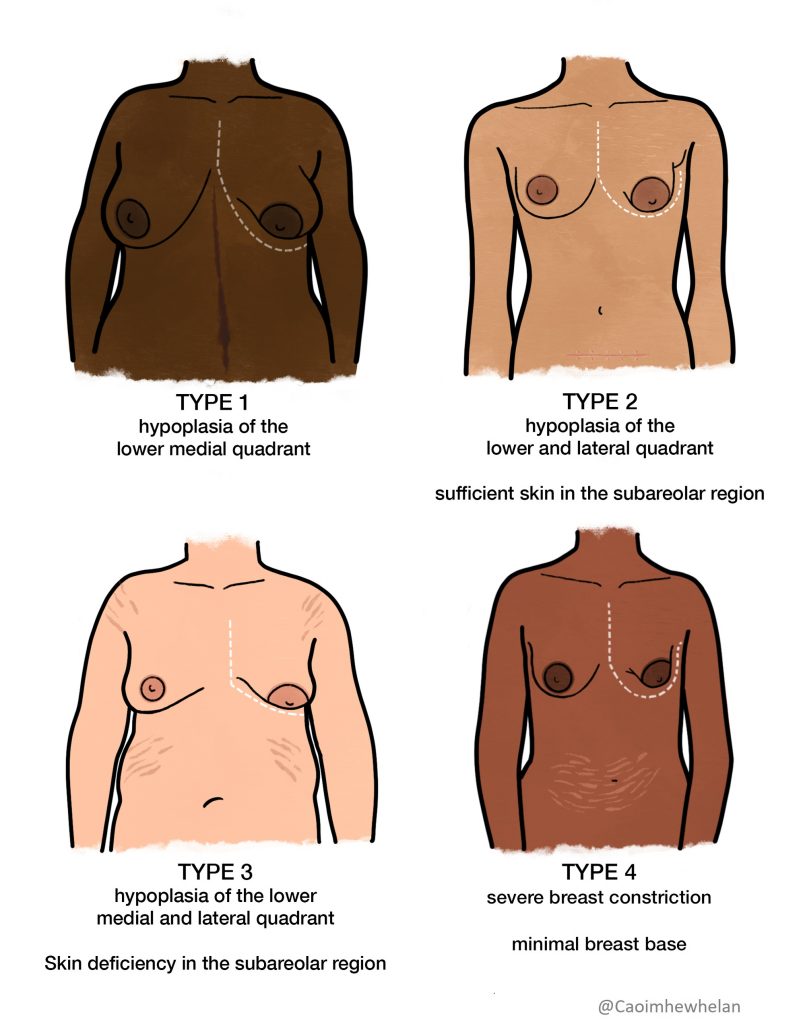

There are only a handful of case studies on breastfeeding with IGT in the literature (Arbour and Kessler, 2013a; Bodley and Powers, 1999; Neifert et al., 1985) and very little research has been done on the causes, diagnostic criteria or the prevalence of the condition. Huggins, Petol and Mireles (2000) conducted a study of thirty-four mothers with breasts suggestive of IGT and classified their breasts as type I, type II, type III or type IV using the Heimburg classification system (Heimburg, Exner, Kruft et al., 1996). They found that 61% of the participants were unable to produce a full milk supply within the first month. The study identified six physical characteristics of IGT which can be used in the antenatal period to identify women who may be at risk of insufficient milk production; lack of breast changes during pregnancy, breast shape, breast asymmetry, stretch marks on the breasts, a wide intramammary space, and areolar abnormalities. The authors highlighted the importance of emotional support for women with IGT who wish to breastfeed to help them work through feelings of anger, guilt, inadequacy and disappointment.

While the Heimburg classification system is useful in identifying IGT as a possible cause of primary low milk supply, it cannot be assumed that all women whose breasts are classified as type I, type II, type III or type IV will be unable to achieve a full milk supply. Lactation consultants in clinical practice often refer to IGT as a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning that all other possible causes of insufficient milk production such as hypothyroisism, polycystic ovarian syndrome or poor breastfeeding management should be ruled out before a diagnosis of IGT is made.

Although there is a glaring lack of research on IGT as it pertains to breastfeeding and lactation, it is well documented in plastic surgery literature on aesthetic breast surgery. These studies tend to focus on the appearance of the breast and the surgical techniques used rather than the underlying pathology. They use a number of different terms to describe breasts that lack glandular tissue or have an abnormal presentation, including breast hypertrophy, hypomastia (Neto, Neto, Abla et al., 2012), breast aplasia (Knackstedt, Deross and Moreira, 2020), tuberous/tubular breast (Zholtikov, Korableva and Lebedeva, 2018), developmental breast asymmetry (Chan, Mathur, Slade‐Sharman et al., 2011), the snoopy deformity (Gruber, Gruber, Jones et al., 1980), and congenital breast deformities/anomalies (Agbenorku, Agbenorku, Iddi et al., 2011).

Despite the dearth of studies on IGT, awareness of how it can impact milk supply and breastfeeding has grown among lactation consultants and mothers over the last decade, as evidenced by the number of IGT and low supply peer-support groups on social media and the number of lactation consultants informally blogging about it. There is currently a support group on Facebook called ‘IGT and Low Milk Support’ which has almost 10,000 members. In addition there was the publication of a book on the topic aimed at breastfeeding women who have IGT (Cassar-Uhl, 2014). However, much of what is known about strategies for breastfeeding with IGT is anecdotal and there remains a gap in the literature on studies on human subjects. According to Kam, Bernhardt, Ingman et al., (2021b), “further research is needed to investigate breast hypoplasia as one reason for a primary insufficient milk supply“.

Deem, H. M., H (1958b) ‘Breast-feeding’, New Zealand Medical Journal, 57, pp. 539-556.

Chan, W. et al. (2011) ‘Developmental Breast Asymmetry’, The breast journal, 17(4), pp. 391-398.

Thanks Caoimhe for this well researched article on this most distressing of phenomena experienced by those wishing to breastfeed. The level of guilt and self blame is huge.

Thanks for this really interesting piece. I am really curious about the environmental factors involved in the disruption of breast development.

Hi Pauline, there isn’t much evidence in human subjects. Here’s a study https://www-sciencedirect-com.ucd.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0890623814001981?via%3Dihub and here’s a few more (let me know if you want me to email you these studies)

Ashrap, P. et al. (2019) ‘In utero and peripubertal metals exposure in relation to reproductive hormones and sexual maturation and progression among girls in Mexico City’, Environmental research, 177, pp. 108630-108630.

Braun, J. M. et al. (2016) ‘What can epidemiological studies tell us about the impact of chemical mixtures on human health?’, Environmental health perspectives, 124(1), pp. A6-A9.

Kelley, A. S. et al. (2019) ‘Early pregnancy exposure to endocrine disrupting chemical mixtures are associated with inflammatory changes in maternal and neonatal circulation’, Scientific reports, 9(1), pp. 5422-5422.

Really interesting article. I have met a few women with breast hypoplasia working as a community midwife. It is so difficult when a woman really wishes to breastfeed and is doing everything possible but her baby isn’t gaining weight and the supply just isn’t there. Are you still doing the zoom every second Monday? Thanks, Claire

Hi Claire thanks. I do a low supply support group every months – I will do one within the next couple of weeks. I post the time and details on my Instagram account. I see a lot of clients with IGT who breastfeed longterm. Caoimhe

Thank you for this blog. I am a mom and I believe I have IGT. My breasts are tube shaped and point down. I know I had estrogen dominance as a child. I was obese. Had one menstrual period at 14 and not another one until my endocrinologist induced a withdrawal bleed.

I was diagnosed with PCOS at that time and averaged 1 menstrual cycle a year until the age of 25 when I started eating low carb and intermittent fasting. That gave me regular cycles and I got pregnant easily.

When my son was born, all the lactation consultants said just keep going, but I knew something was wrong. With in days, my son was dehydrated, with no wet diapers. I had met with several lactation consultants at the hospital who said my latch was good and I was doing everything they said including triple feeds every two hours, which was killing me.

I did my own research and asked my lactation consultant if I had IGT. She said it was possible, but she couldn’t diagnose me. I asked my OBGYN to diagnose me and she said she’d “never heard of it. Just give him formula.” It was such a frustrating and lonely experience. I felt like noone believed me. They acted like I wasn’t trying hard enough.

I could feel milk in my breasts when I woke up in the morning, but it was only in a small area right behind my puffy areolas. I could get about 1/2 ounce max if I pumped.

It feels so good to be validated in my experience.

Hi Diana, I’m so glad you found this article helpful. There’s a widely-held belief that low supply is always ‘perceived’, which can be very frustrating for women like yourself who are physiologically unable to produce a full supply. Hopefully in time there will be more research on this area of lactation which will help shape better supports for those who have primary low milk supply.

Great article! I believe I have Type 1 IGT and I am currently breastfeeding. My 4 week old is attached all the time but eventually she manages to grow nearly 200gr per week. If I were diagnosed with IGT, can I hope to be a lucky one and keep breastfeeding my baby or will my supply hit a limit anytime soon?

Thanks

Hi Carmen, fantastic that breastfeeding is going so well for you! Well done. It’s impossible to predict what your supply will be like in weeks to come, but either way you can still keep breastfeeding. If you encounter challenges, try to link in with some skilled breastfeeding support. best of luck, Caoimhe

Hi Caoimhe,

Thank you for your article. I was diagnosed with IGT by an excellent lactation consultant a month post-partum. I couldn’t understand why breastfeeding was so hard and I felt a great deal of guilt and frustration that all my efforts couldn’t yield more than 40mls at a time. I turned against breastfeeding for a long time after that, convinced that everyone breastfeeding was just powering through where I couldn’t. It definitely had an impact on my mental health at the time.

My mother also had similar issues when she had me. It’s interesting that the cause could be environmental, as I assumed that it was purely genetic. I hope my daughters will be able to breastfeed (or have the option to).

Many thanks for tackling this issue,

Rebecca

Hi Rebecca – I did research on women’s experiences of breastfeeding with low milk supply. Of the 9 participants (all of whom reported IGT, or suspected IGT), 3 said their mothers also struggled to produce enough milk. We really need more research to understand the causes of IGT.

Another finding was that all of the mothers said their mental health was impacted by having IGT/low supply. It’s such a difficult thing to experience and can take a long time to process and make peace with. x

Hello,

My daughter is now 6 weeks, and I was diagnosed about 3 weeks ago. I still have hope that I could at some point exclusively breastfeed. I breastfeed and supplement 40-60ml after each breastfeeding, and my daughter keeps gaining weight (0.25-0.33kg per day). But I can see that she struggles with my low supply. My concern is mostly when she will grow and need more (how to know how much formula to give her?) She has cow protein intolerance and needs to take a very special (and expensive) formula. I am doing all I can increase my supply, so that she does not have to get too much of formula

I believe you have a zoom support group. I am in Canada (Montreal), but would love to join this group. Is this possible?

Hi Geraldine,

I’m so sorry for the delay in getting back to you. I don’t check my website that often. You are very welcome to join the low milk supply group – we should have one in a couple of weeks. I will post details on Instagram and Facebook. There is also a low milk supply WhatsApp support group – if you email me at caoimhew@gmail.com I can send you the QR code to join. xCaoimhe